COVID-19: Are Clinicians Ready for a Viral Pandemic?

페이지 정보

작성자 소겸 댓글 0건 조회 1,483회 작성일 20-03-21 17:33본문

Note: This is the ninth of a series of clinical briefs on the coronavirus outbreak. The information on this subject is continually evolving. The content within this activity serves as a historical reference to the information that was available at the time of this publication. We continue to add to the collection of activities on this subject as new information becomes available.

Clinical Context

Emerging pathogens pose a challenge and are a global public health concern. They often emerge with limited data on characteristics and epidemiology, escaping standard laboratory testing and treatment, which leads to lack of containment, resulting in an outbreak and then, if on a large scale, a pandemic.

COVID-19 continues to spread around the globe with more than 150 countries impacted. The number of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases has risen exponentially, going from 282 to more than 182,000 in the couple of months that have passed since the World Health Organization (WHO) started tracking it in January 2020. As of March 17, there have been more than 7000 deaths resulting from COVID-19. In cases identified within the United States, the number of confirmed and presumptive cases related to person-to-person spread has grown larger than the number of travel-related cases.

As the number of confirmed cases continue to grow exponentially, the WHO marked this monumental event by reminding all countries and communities that executing robust containment and control activities can significantly slow or reverse the spread of this virus.

How can clinicians help lead the way in COVID-19 preparedness?

Synopsis and Perspective

A pandemic is a global outbreak of a new virus. Pandemics happen when new viruses emerge that are able to infect people and spread from person to person in an efficient and sustained way. Very few people have immunity against a pandemic virus because it is new to humans, and a vaccine may not be widely available. Often the characteristics of the virus are not well defined, and the extent of infection will depend on whether or not humans have immunity to that virus, as well as the health, age, and comorbid conditions of the person being infected.

A key example is the most recent pandemic of 2009 with H1N1. According to the CDC, when it emerged, the H1N1pdm09 virus differed from previous H1N1 viruses not only in characteristics but also in the population it infected. The genes of the virus were a unique combination of influenza genes that had not been previously identified in either animals or people. At the time, it also affected people younger than 60 years who had not built up immunity to previous H1N1 viruses (as was the case in those aged 60 years and older). As a result, the seasonal influenza vaccine offered at that time had little preventative effect. An estimated 151,700 to 575,400 people worldwide died from H1N1pdm09 virus infection during the first year of that pandemic. Consider that in a typical seasonal influenza epidemic, about 70% to 90% of deaths are estimated to occur in those aged 65 years or older. In the case of global H1N1pdm09 virus-related deaths, however, 80% were estimated to have occurred in people younger than 65 years.

In 2009, when the US government determined that a public health emergency existed nationwide, plans to begin stockpiling supplies to protect and treat influenza were initiated. The CDC archived data indicate that supplies included 11 million regimens of antiviral drugs and more than 39 million respiratory protection devices (masks and respirators), gowns, gloves, and face shields. The CDC's Strategic National Stockpile allocated these supplies on the basis of each state's population.

As the world faces the COVID-19 pandemic now in 2020, this is the time for local governments and health departments to prepare. Healthcare providers should review infection control procedures, especially related to protocols, isolation, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Fast and effective preparation is essential, and there is a key first step clinicians need to take: fighting denial.

In a 2019 statement published in Infection Control Today, when addressing the topic of a pandemic, Tener Goodwin Veenema, PhD, MPH, RN, an international expert on disaster preparedness and containment of outbreaks and a professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, stated, "Any hospital or healthcare organization needs to make sure that what they are doing is completely consistent with the gold standards published by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OHSA) and the [CDC]."[1]

She further stated: "The key is how do we made sure that we create an infection control program and have [a PPE] plan that is consistent with national guidelines and positions us to keep our patients, staff, and visitors safe"?[1]

The following are critical steps that clinicians need to take to protect themselves and their communities.

Personal Preparedness and Personal Safety Are Key

Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection

Viruses have the ability to contaminate hard surfaces, which plays a key role in transmittance between people. At this time, it is unknown how long SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, remains active on surfaces. Healthcare providers should use effective disinfectant products for use against emerging viral pathogens, especially in patient care areas. The CDC recommends that products approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency (with the external icon) should be used against SARS-CoV-2. Other areas that need to ensure appropriate number of supplies include materials management, laundry, food services, and medical waste. Use of these should be addressed in accordance with routine procedures. Aerosol-generating procedures also should be performed. This includes collection of diagnostic respiratory specimens in an airborne infection isolation room while following appropriate infection prevention and control practices, including use of appropriate PPE.

Best practices for environmental cleaning in healthcare facilities in resource-limited settings, provided by the CDC, can be found on the CDC website.[2]

The CDC also has provided recommendations to healthcare personnel (HCP) caring for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infections. Practicing how to appropriately use personal protective equipment is high on the list.

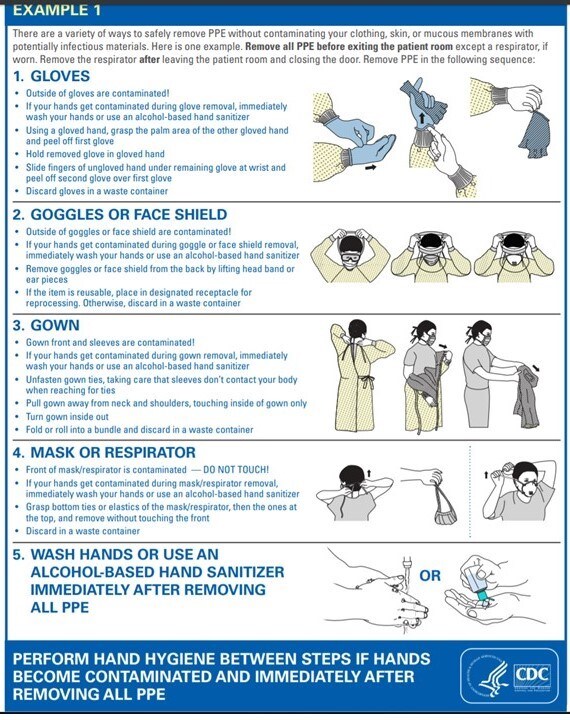

Stressing the importance of exposure from self-contamination resulting from improper removal of PPE, Dr Goodwin Veenema stated "Donning and doffing is critically important."[1]

Education about PPE for healthcare and support staff is just as important as adequate policies, procedures, and supplies. Healthcare providers are front and center in a pandemic, and there is a need for healthcare facilities to stress the importance of self-protection at all times, especially during a viral outbreak.

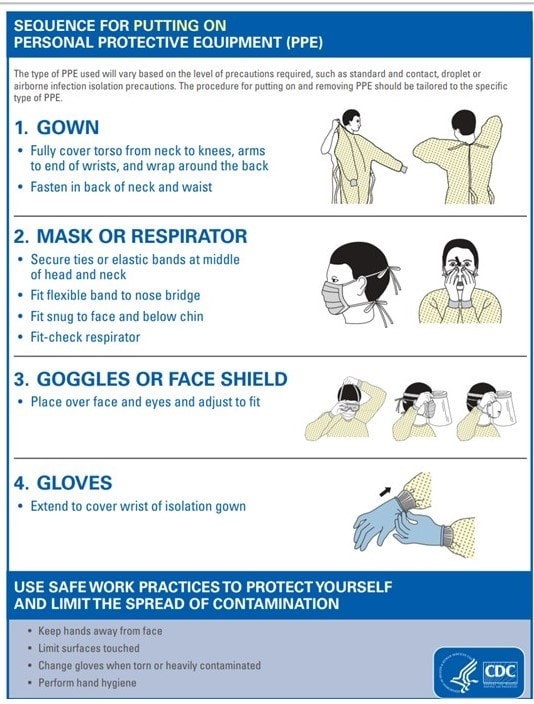

The CDC has provided guidance on putting on PPE, visualized in the following images:

Note that the type of PPE used varies on the level of precaution that is required for that specific isolation type (ie, standard and contact, droplet or airborne infection).

In the healthcare setting, to contain the spread of pathogens, a key infection prevention for all isolation types is to ensure PPE are donned on entering patient's room and discarded properly before exiting. Transportation and/or movement of patients outside the designated isolation room should be kept at a minimum, and only when medically necessary. Disposable or dedicated patient care equipment should be used when possible. If there is a common use for equipment (ie, multiple patients), equipment should be cleaned and disinfected between uses). The single most important and effective advice that health experts give is to implement good hand hygiene practices.

For contact precautions, in addition to ensuring appropriate patient placement (ie, isolation), clinicians should ensure gowns and gloves are worn for all interactions that involve contact with the patient or patient environment. Prioritization should be given to cleaning and disinfecting rooms and surfaces.

Source control should be at the top of the list in managing both droplet and airborne precaution (ie, putting on a mask or putting a mask on a patient). Proper respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette should be followed at all times for droplet precautions. For airborne precautions, patients should be placed in an airborne infection isolation room. Susceptible persons should be restricted from patient rooms suspected of having measles, chickenpox, disseminated zoster, or smallpox. For airborne precautions, a primary PPE goal is fit testing for National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health-approved N95 or higher-level respirator for HCP. Detailed isolation precautions guidelines are available on the CDC website.[3]

Laboratory Testing

CDC testing kits were a game changer in the fight against H1N1 in the 2009 pandemic. For laboratories that are testing specimens for COVID-19, appropriate PPE should be used in collecting and handling specimens. Laboratories should use CDC interim guidance for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from persons under investigation for possible COVID-19 infection.[4]

"Remember to create a program where we are really stressing personal preparedness and personal safety," Dr Goodwin Veenema said. "Encourage all healthcare providers and anyone who works within the hospital to make sure they have a flu shot annually, and to remember that the number one best strategy for infection control is adequate handwashing."[1]

All healthcare professionals should be preparing to potentially evaluate patients with COVID-19, with an emphasis on infection control.

During this pandemic, patients and their communities will be looking to clinicians for guidance.

"People will differ in the risk-benefit trade-offs they choose, and physicians can help them assess what choices they are making," said Baruch Fischhoff, PhD, a cognitive psychologist and decision scientist.

"As a physician on the front lines, it may become imperative to wear a mask both to set an example and for safety reasons," he told Medscape Medical News.

Good old-fashioned hand washing and alcohol wipes remain a priority, he says, and "any patient with chronic illnesses or respiratory problems, acute or chronic, are going to have to be extra cautious. This means in addition ..... they are going to have to limit exposure to large groups of people."

What should clinicians tell their patients about stockpiling?

"For the most part, I don't think people are overreacting," Seth Gordon, MD, a Manhattan pediatrician, told Medscape Medical News. "Stocking up on essentials, whether that be food or necessary meds, is also appropriate to a reasonable degree. An ounce of prevention goes a long way, and if we are all pulling in the same direction, it goes even farther."

What are some key things that clinicians know about PPE?

The CDC offered clarification on some concerns that have come up concerning PPE for healthcare team members caring for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19:

- Transmission of pathogen during the procedures performing nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs on patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: The CDC recommends that in addition to being well trained in the procedure, clinicians should don a clean, nonsterile, long-sleeve gown, medical mask, gloves, and eye protection (ie, goggles or face shield). Although there is concern about patients' coughing and transmitting the virus, the CDC states there is no proven evidence of aerosol transmission of COVID-19 via coughing. Patients should be advised to follow infection prevention practices such as covering their mouth while coughing.

- Routinely wearing PPE for all patients (such as boots, impermeable aprons, or coverall suites) who have suspected or confirmed COVID-19 respiratory infections: At this time, the WHO recommends the use of contact and droplet precautions, in addition to standard precautions for all patients. PPE for contact and droplet precautions as outlined here includes wearing disposable gloves to protect hands; clean, nonsterile, long-sleeve gowns to protect clothes from contamination; medical masks to protect nose and mouth; and eye protection (eg, goggles, face shield). These should be donned before entering the room of any patient suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19 acute respiratory disease. The WHO clarified that respirators are only required for aerosol-generating procedures.

- Sterilizing and reusing disposable medical face masks and gowns: These items should be for 1-time use only. The CDC recommends that disposable face masks should be removed and disposed of immediately in an infectious waste bin with a lid, using appropriate hand hygiene techniques. The CDC directs that in removing the mask, healthcare workers should be careful not to touch the front of the mask and should remove the mask by pulling the elastic ear straps or laces from behind. The WHO also clarifies that routine wearing of masks for healthy people is not necessary. There is currently no evidence that supports routine use of masks in asymptomatic persons in the community (those who do not have respiratory symptoms of illness). They do indicate that symptomatic persons in the community should wear medical masks.

- N95 respirators should NOT be used instead of surgical masks by the public. As defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), N95 respirators are protective devices used for respiratory illnesses which “are designed to achieve very close facial fit and very efficient filtration of airborne particles”. These are regulated by the CDC and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). They are manufactured for use in healthcare and in construction (or other industrial type jobs). Those that are used in the health care setting are classified as class II devices. According to the FDA notice on these respirators, they are known to block at least 95 percent of very small (0.3 micron) test particles. As such, they are known to exceed those of face masks if properly fitted because of their high filtration capabilities. However, the FDA cautions that this does not ensure complete elimination of illness or death.

- Surgical masks and N95 respirators are regulated by the FDA. The clear difference between them is that the edges of the surgical mask are not designed to form a seal around the nose and the mouth. This is different from the N95 respirators which are designed to be a very close facial fit and have superior filtration of airborne particles as previously explained. The FDA indicates that the similarities between both is that they are both tested for fluid resistance, particulate and bacterial filtration efficiency, biocompatibility and flammability. Additionally, both are labeled as single use, disposable devices and should not be shared or reused. An infographic of the differences between the two, can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/UnderstandDifferenceInfographic-508.pdf

- The FDA cautions that N95 respirators are not designed for children or people with facial hair as it may not ensure proper fit and thus full protection. N95 Respirators should generally not be worn by the public. CDC does not recommend this as it does not offer any additional health benefit against COVID-19 infection. Everyday preventive action (i.e handwashing) is the optimal way to prevent airborne transmission of COVID-19 in this pandemic, not just relying on PPE alone.

In times of a pandemic, having supplies of masks available is essential for those who actually need them. To prevent serious issues of shortage and availability, clinicians should discourage the misuse and overuse of medical masks.

The CDC recommends that if you have an unprotected exposure (ie, are not wearing recommended PPE) to a patient with confirmed or possible COVID-19, this should be reported immediately to occupational health. In addition, if you develop symptoms consistent with COVID-19 (fever, cough, or difficulty breathing), this should be reported as well.

The CDC has issued guidelines to establish current best practices in limiting the effect of COVID-19 in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/healthcare-facilities/guidance-hcf.html

Full guidance on infection prevention for epidemic- and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infection in healthcare can be found on the WHO website.[5-8]

Highlights

- Gowns should be worn by HCP in the evaluation and treatment of a patient with possible COVID-19 infection. In cases of invasive procedures that might put HCP in contact with blood or bodily fluids, isolation gowns with a high degree of protection are recommended. For routine care, gowns with low or minimal barrier protection are sufficient.

- HCP should follow their institution's recommendations regarding putting on and taking off (donning and doffing) PPE. Failing that, they provide a resource to demonstrate best techniques: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/PPE-Sequence-508.pdf

- Hand hygiene with soap or an alcohol-based rub is essential before putting on and after taking off PPE.

- Coveralls, which typically include 360-degree protection for the entire body, are acceptable alternatives to gowns and may be necessary in medical transport of potential cases of COVID-19. However, coveralls are more difficult to put on and take off safely vs gowns, and they can be uncomfortable.

- Nonsterile disposable examination gloves are recommended when examining patients with suspected COVID-19 infection. Double gloving or using extra-long gloves is unnecessary.

- The CDC does not recommend the use of respirators outside of healthcare settings.

- Patients being evaluated for possible infection with COVID-19 should wear face masks to prevent the dispersion of large particles. Once the patient is isolated in the healthcare facility or home, their face mask may be removed.

- HCP attending these patients should wear N95 respirators, which effectively filter large and small particles. Surgical N95 respirators should be worn in cases of potential airborne and fluid hazards by healthcare workers. The CDC specifies the use of N95 respirators for health care workers only. They do not recommend they be worn by the general public to protect themselves from COVID-19 as they site no added health benefit.

- Shoe or boot covers are not necessary in the routine evaluation and management of patients with COVID-19.

Clinical Implications

- As of March 17, more than 150 countries have reported laboratory-confirmed cases of COVID-19, including the United States. The number of confirmed cases worldwide has risen exponentially, going from 282 to more than 182,000 in the few months that have passed since the World Health Organization (WHO) started tracking it in January 2020. There have been more than 7000 deaths resulting from COVID-19.

- PPE for the evaluation and management of COVID-19 should include a full-face shield or goggles, a gown, an N95 respirator, and gloves. Shoe or boot covers are unnecessary.

- Implications for the Healthcare Team: Infection control requires a team approach to reach success. All team members should be aware of PPE required in clinical settings in cases of COVID-19 infection.

관련링크

댓글목록

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.